By Sriram Sarvotham┃Posted: April 28, 2019

The practice of yoga brings numerous benefits (here are 77 of them!). One striking observation is that some of the benefits appear seemingly opposite; but in fact they’re complementary.

The words “hatha yoga” – which encompasses most of the yoga practices involving postures, breathing and meditation – can be translated to mean “sun-moon yoga” (“Ha” = sun, “tha”=moon. There are other meanings of “hatha” as well.). In the context of yoga, sun represents energy and moon represents relaxation.

Complementary benefits

Yoga gives equal emphasis on the seemingly opposite yet complementary aspects: energy and relaxation. This plays out in yoga practice in many ways. For example, in asanas, stretching poses relax the muscles, while tensing poses strengthen the muscles.

In breath-work, certain practices (kapala bhati, bhastrika, etc.) induce energy and “heat” in the system, whereas others (ujjayi, sheetali, etc.) provide a calming effect. Inner practices also involve complementary disciplines. For example, concentration (dharana) and meditation (dhyana), respectively, involve the ability to focus the mind and settle the mind to tranquility.

Other examples include equal emphasis on left and right brain development, sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, prana (rising life force) and apana (descending life force), etc. In this regard, yoga is a well-rounded discipline that develops all dimensions of health and well-being.

The relationship between sensitivity and strength, the topic of this blog post, is one more example of the many complementary benefits.

Sensitivity

I find it remarkable that yoga caters to both these aspects of well-being. Many physical fitness disciplines focus on one of these two aspects, but very few attend to both.

What is sensitivity? The dictionary definition is- “the ability to detect or respond to slight changes, signals, or influences.” In yoga, we’re encouraged to listen to the body, to the breath, and to our ”self.” When we do a yoga posture, we check with the body; is the body experiencing harmony, stability, comfort? The body’s intelligence provides signals, in the form of sensations, to let us know about its well-being or lack thereof.

Why is it a good idea to be sensitive and listen to the body? The human body is an extraordinary mechanism that has the ability to find its equilibrium and heal itself of any discomfort. However, in some cases the body’s intelligence needs our assistance, and sends indicators and sensations to alert us. For example, when the body is depleted of nutrition, we feel the sensation of hunger. Likewise, when the cells of the body are overworked, we feel the need to rest. Even the sensation of pain is an indication from the body we can benefit from (here is a lovely article on this).

In yoga, we nurture this ability to sense the body. We become more keenly aware of subtle sensations. There’s no need to wait for the discomfort to intensify before we sense it and make amends! In fact, when we heed the “whispers” from the body, we can prevent future manifestations of illness and disease; we destroy the seeds of disharmony before they sprout and take root. Maharishi Patanjali mentions this in his Yoga Sutras: ”Heyam duhkham anagatam,” meaning the future manifestations of misery can be avoided with yoga.

In other words, we can use the indications from the body’s intelligence as a guide to move towards harmony and away from disharmony. One practical situation where this can be applied is in our food habits. Listen to the body’s intelligence, and notice how the body responds when we ingest specific foods. The response will be very different between junk food and nutritious food!

Yoga postures help to sharpen our sensitivity to our body. In each pose, specific parts of the body are attended to (including internal organs), and spring up into our awareness as sensations originating from those parts. In a well-rounded sequence of postures, we systematically listen and attend to every part of the body.

Sensitivity isn’t just limited to listening to the body. We also develop sensitivity to our breath (breath is an indicator of struggle or ease), and our soul. Just as postures help us to be sensitive to the body, meditation helps us to be sensitive to our “Self.” We can use inner guidance to align our thoughts and actions with our deepest intentions. For example, when we become lazy and lethargic, we feel rotten, and the uneasy feeling is guidance to make changes. Another example is unethical behavior. When we’re sensitive to the inner “Self” and heed its messages, our actions can never be unethical; our “conscience” guides us towards thoughts and actions that express human values such as friendliness, compassion, love, gratitude, courage, peace, etc.

Strength

Sensitivity is only half of the equation. The complementary aspect, namely strength, is also nurtured in the practice of yoga. The dictionary provides numerous definitions of strength; here are a few that are relevant to the topic here:

1. Ability to withstand great force or pressure.

2. Not easily affected by disease or hardship.

3. Not easily disturbed or upset.

4. Showing determination and self-control.

Several yoga postures develop strength in the body (like upward dog and downward dog), but the strength isn’t restricted to muscular strength. Many postures help strengthen internal organs. For example, paschimottanansana (posterior stretch) and ardhamatsyendrasana (classic seated spinal twist) strengthen the digestion, as mentioned in the yoga text Hatha Yoga Pradipika.

Furthermore, Patanjali mentions that the practice of asanas helps strengthen the system to withstand “pairs of opposites” like heat/cold, etc., when he refers to the dvandva (divisions or opposites) anabhigathaha (not getting affected by it).

Mental strength is developed in yoga by several pranayamas. The quality of awareness can be elevated and made “bright” using pranayamas and kriyas. Furthermore, inner strength can be developed through the practice of dharana (concentration), which forms the 6th limb of the 8 limbs of (ashtanga) yoga.

When we develop sensitivity without strength, we experience discomfort more intensely if we place ourselves in an unfamiliar or rough environment. For example, a person who is very sensitive to food but lacks strong digestion may sense acute discomfort when they consume food in a new place (parties, restaurants, etc.). Or a person sensitive to the weather can easily develop discomfort or illness when there’s a sudden change in weather or while traveling. Similarly, when we’re keenly sensitive to our inner guidance but lack mental strength, we easily get bogged down by mild criticism or a when handling challenging situations.

In like manner, strength without sensitivity isn’t conducive towards optimal well-being. For example, students of yoga with strong determination to perfect a posture (to be photogenic & perfect) could injure themselves if they don’t heed the body. Likewise, one with inner strength who lacks sensitivity could inadvertently hurt others by expressing truth without compassion.

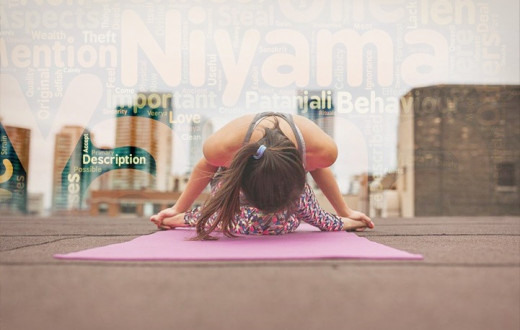

Patanjali’s “Yoga Sutras”

Maharishi Patanjali makes references to strength and sensitivity. The practices of tapas and svadhyaya are closely related to strength and sensitivity.

Tapas literally means heat, and refers to the discipline and austerity of the yoga practices. Patanjali mentions two benefits of engaging in tapas: it purifies the system and strengthens the system to perform at its peak form. Svadhyaya means self-study (sva= self, adhyayana=study). It refers to the study of the self: the body, breath, mind, “Self,” and listening closely to sensations, and their guidance that comes forth. (There’s another meaning of svadhyaya: self-directed study of scriptures).

Tapas and svadhyaya are two of the five components of niyama (personal observances, or personal responsibilities), which forms the 2nd limb of yoga. They’re also ingredients of Patanjali’s Kriya Yoga – yoga of action.

Patanjali also mentions valour and strength to experience yoga. He suggests a way to develop this virya, namely by living our highest, being established in the highest consciousness (brahmacharya, which literally means moving in brahman).

Let me close with a sutra from Patanjali that describes 4 physical benefits of yoga practice. The first two relate to sensitivity and the last two relate to strength.

“Roopa lavanya bala vajrasamhananatvani kaya sampat,” meaning beauty (roopa), grace (lavanya), strength (bala), and strong constitution (vajra samhanana) are the physical benefits of practicing yoga.

This article was originally published on Sriram’s Blog and is re-posted here with the author’s permission.

Shriram Sarvotham, a yoga teacher since 1991, holds a Ph.D. degree in Electrical Engineering from Rice University, Houston, TX. He works in the tech industry in Silicon Valley California.